About John Marin

In 1948, a Look magazine survey of museum directors, curators, and art critics selected modern watercolorist John Marin as the greatest painter in the United States. Marin’s early years had not promised any such recognition. Until he was nearly forty, he was unsure of how he wanted to make his living. The young Marin shifted between working for a whole sale notions house, training and working as an architect in his native New Jersey, and attending the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and then the Art Students League in New York. From 1905 to 1909, he lived in Paris and made picturesque etchings of European architecture for the tourist trade. But one overriding passion was always there for Marin – drawing. He said, “I just drew. I drew every chance I got.” 1

In 1908, Edward Steichen, a modernist American photographer and painter, saw Marin’s watercolors on exhibition in Paris at the Salon d’Automne. Excited by what he saw, Steichen arranged for Marin’s first exhibition at 291 Gallery, the chief outpost of modern art in New York City. A few months later, the proprietor of 291, photographer Alfred Stieglitz, met Marin in his Paris studio. Stieglitz became not only Marin’s regular art dealer and promoter, but also his mentor and close friend.

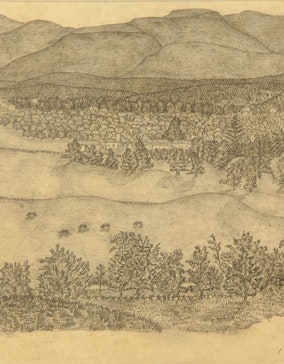

When Marin returned to the United States briefly in 1909, and permanently in 1910, the artist established himself as a cutting edge modern artist. Marin’s art appeared annually at Stieglitz’s succession of New York modernist galleries, 291, The Intimate Gallery, and An American Place, for most of his career. Stieglitz supported Marin’s use of watercolor, although the medium was generally seen as less important and substantial than oil paintings on canvas and collectors would pay less for watercolors than for oils. Marin’s gestural watercolors of the architecture of New York City and the rural scenery of Maine, and his etchings, became some of the most admired works Stieglitz exhibited.

Marin settled in Cliffside, New Jersey, and had his studio there during most of the year. Beginning in 1914, Marin and later his wife, Marie, and son, John Marin, Jr., spent most summers in Maine. Critics lauded Marin’s watercolors in newspapers and magazines, and collectors avidly sought his work. Marin also made oil paintings on canvas, but he was best known for his watercolors.

Fewer strokes, still fewer strokes. Fewer strokes must count.

John Marin to Alfred Stieglitz, September 28, 1916

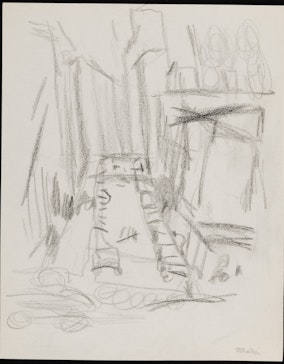

A full mellow ring to each stroke.

Marin’s drawings sometimes appeared in exhibitions, but most were informal private documents made for his own creative purposes. He made few drawings in rural places, where he could work undisturbed and simply make a watercolor on the spot without a preparatory sketch. Marin preferred to sketch on the teaming sidewalks of New York where he could not have set up an easel to make a watercolor without being constantly bumped and questioned. He said of his urban drawings, “the drawings — were mostly made in a series of wanderings around about my City — New York — with pencil and paper in — short hand — writings — as it were — Swiftly put down”. 2 Most of these New York drawings were made on cheap 8 × 10-inch writing pads that the artist could afford to buy in large numbers. Marin kept piles of sketchbooks that he consulted as sources for finished works he made in his studio.

Arthur Rothstein (American, 1915-1985), John Marin in His Studio, Hoboken [sic], New Jersey, 1949, gelatin silver print from the portfolio Arthur Rothstein, 1981, 9 3/16 × 15 15/16 inches (23.3 × 40.5 cm), the Art Institute of Chicago, Gift of Elizabeth and Frederick Myers, 1983.1567, The Art Institute of Chicago / Art Resource, NY

Some of Marin’s drawings were tightly detailed architectural renderings such as he had learned to make as an architect. Other drawings were experiments in visually fragmenting forms to creative expressive modernist compositions. But most of Marin’s New York City drawings were quick, vigorous notations recording the forces and motions he felt in the buildings and figures around him.

Marin said, “When one speaks of drawing — what does one mean to convey[?] Does it not derive from motion gestures[?]” 3 He asserted, “Drawing is the path of all movements Great and Small — Drawing is the path made visible.” 4 In his watercolors of skyscrapers rising in New York City and the winds and trees on the coast of Maine, Marin traced the paths of motions he saw and felt in brilliant colors.

Marin’s work gained increasing critical attention as the years passed. Many museums exhibited and acquired his work. In 1936, he was accorded the honor of one-man retrospective exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Marin continued to live and work in New Jersey, and to vacation in Maine, even after the artist suffered a heart attack in 1946. Alfred Stieglitz died in the same year. Marin worked with Stieglitz’s widow, artist Georgia O’Keeffe, to run An American Place, Stieglitz’s last gallery, for the next few years. John Marin died on October 1, 1953, at his beloved house on the rocky shore of Cape Split, Maine.